Inside Superfine: Tailoring Black Style

On Brooks Brothers’ past, female dandies, Sinners + a Q&A with Monica L. Miller

The rich kids I went to high school with had one thing in common: they did not care much for their appearance. Some of them showed up to class disheveled, sometimes in the same nondescript shirt they wore the day before, not noticing the occasional food or underarm sweat stains. “What a privilege it is to not care,” I thought.

I could have let myself go and not put as much thought into my outfits but I couldn’t do it. Call it status anxiety or race consciousness (as one of a handful of Black people in the entire school) but I took pride (and pleasure) in going the extra mile. The new girl loved fashion as much as she loved philosophy so putting together a different outfit every morning did not feel like a burden. I enjoyed this early exercise in performing dandyism.

If the dandy is, as Monica L. Miller told us during our private tour at the Met museum last week, “someone who studies above everything else to dress elegantly and fashionably,” the Black dandy is a student by necessity. This is the overarching message of Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, the exhibition Monica guest-curated, based on her seminal book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity.

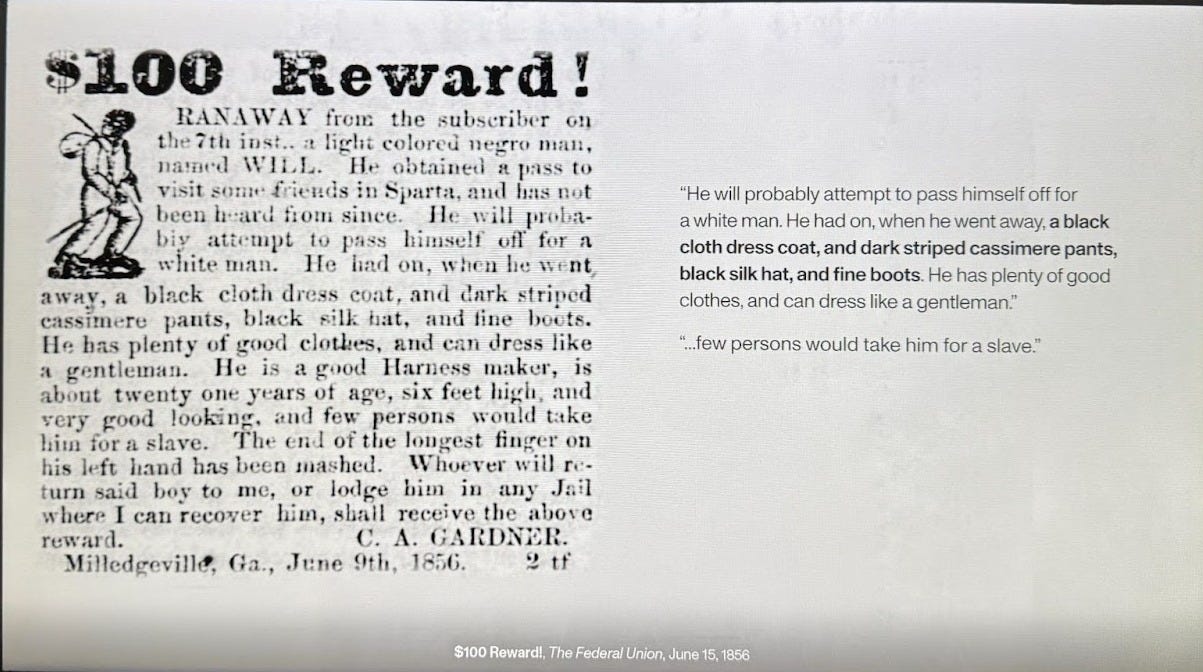

As Black people, when we show up somewhere in our Sunday best, we echo the legacy of our ancestors, utilizing clothing as a negotiation tool, a means of survival, resistance and self-actualization. We project elegance and style in our finely tailored suits, garments our ancestors saw as symbols of freedom and rarely had the luxury of owning. Formerly enslaved author and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano wrote in 1789, “I laid out above eight pounds of my money for a suit of superfine clothes to dance with at my freedom.” This history is so embedded in us, it’s become a sort of psychic connection that we carry in every space. As Monica told me, “When you’re walking as a Black person, you have all your ancestors and your descendants with you.”

Superfine chronicles Black dandyism’s roots in colonialism, starting with the attire of “luxury slaves,”in eighteenth-century Europe and North America, whose livery coats were conspicuous symbols of ownership, and evolving into a global movement of self-determination through fashion. It is a feat of storytelling, rich in substance and thought-provoking in every detail. I loved the story of the mannequin heads; they were made by the artist Tanda Francis, who modeled them after André Matsoua, a Congolese political leader who is widely regarded as the first Sapeur.

Superfine is ultimately a story about the humanity of Black people. It challenges assumptions and unearths hidden histories in hopes that the rest of the world sees us—really sees us as humans, too.