African Jersey Season in Full Effect

How the country jersey has moved into the realm of protest fashion

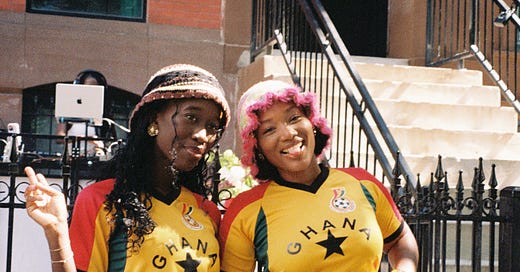

When my sister’s roommate traveled to Ghana last December, she brought her back a football jersey drenched in colors of the flag and bearing the country’s name. When they both wore the shirt to their annual stoop party in June, everyone wanted to buy it. It was a hit.

Many of the guests wore Black country jerseys to the party too, in line with the pan-African dress code. Some people represented the countries they are from; others, like Chris and her roommate, embraced a country they either love, wish to visit or feel a cultural connection to. It was a beautiful celebration of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora in a Brooklyn neighborhood that was once an enclave of Black creativity. I wore a Jamaican-themed halter crop top, not because I’m from Jamaica but because the music, cuisine and island culture all speak to me.

I have since been spotting various country jerseys all over New York City, particularly in neighborhoods where Black people traditionally live and socialize (i.e. Bed-Stuy, Flatbush, East and West Harlem). While I remember elderly Haitians rocking their favorite team jerseys for watch parties in the early 2000s, I am now seeing younger people wearing these shirts as patriotic statements. The subculture has made its way to Black urban life, becoming a powerful vessel of social belonging. At a time when anti-immigration rhetoric continuously runs rampant, the embrace of the country jersey has become its own form of protest, a way of asserting oneself in the face of xenophobia and ignorance.

Fashion entrepreneur and model Michelene Auguste tells me the country shirts sell really well at her store Studio Dem in Williamsburg. “They serve as a way to proudly express our heritage and let others know, ‘This is where I'm from, and I'm proud of it.’”

Mainstream retail is slowly catching on to their importance: Conner Ives, Urban Outfitters, PacSun all offer the style, but tops bearing non-white countries’ names are harder to come across. These still live on the fringe, available mostly at niche retailers or African and Caribbean markets, suggesting a disparity in cultural representation. Ghanaian entrepreneur Paakow Essandoh is increasingly filling the void through his clothing line MIZIZI. “With the growing population of African immigrants not just in the States but worldwide, there’s a hunger for cultural artifacts and our items help represent those cultures,” he said.